Spinning in circles

I’ve been listening to a lot of podcasts lately. I spend a lot of time in the car, and I have also been doing a lot of house projects. One of my favourite bike related podcasts is Fast Talk. I enjoy the host Trevor Connor’s approach to coaching and riding, and the show is based out of the Colorado Front Range, so I generally have first-hand knowledge all of the climbs and rides they are talking about. It’s kind of fun. So Spotify randomly selects podcasts for me to listen to, and it’s this one:

/https://www.fasttalklabs.com/cycling-in-alignment/how-to-pedal-a-bike-with-chris-case/

If you have two hours I’d encourage a listen, and you haven’t already listened to this rather old pod cast. It’s a great discussion. In this episode Colby Pearce sits down with Chris Case to discuss the seemingly simple discussion of “how to pedal a bike”. I should also mention that I generally really like Colby Pearce’s approach to bike fitting. The discussion starts off with Colby asking Chris openly how do you pedal a bike? He’s a bit antagonistic as he asks? But the two have a history and good rapport, it’s all in good fun and for the benefit of an engaging discussion. But Colby goads Chris, prefacing the question with “I know you don’t know how to pedal a bike”. Now, Chris is an accomplished cyclist, so it’s a seemingly absurd assertion, Chris obviously is very good at pedalling his bike, thank you very much. But it’s all in good fun.

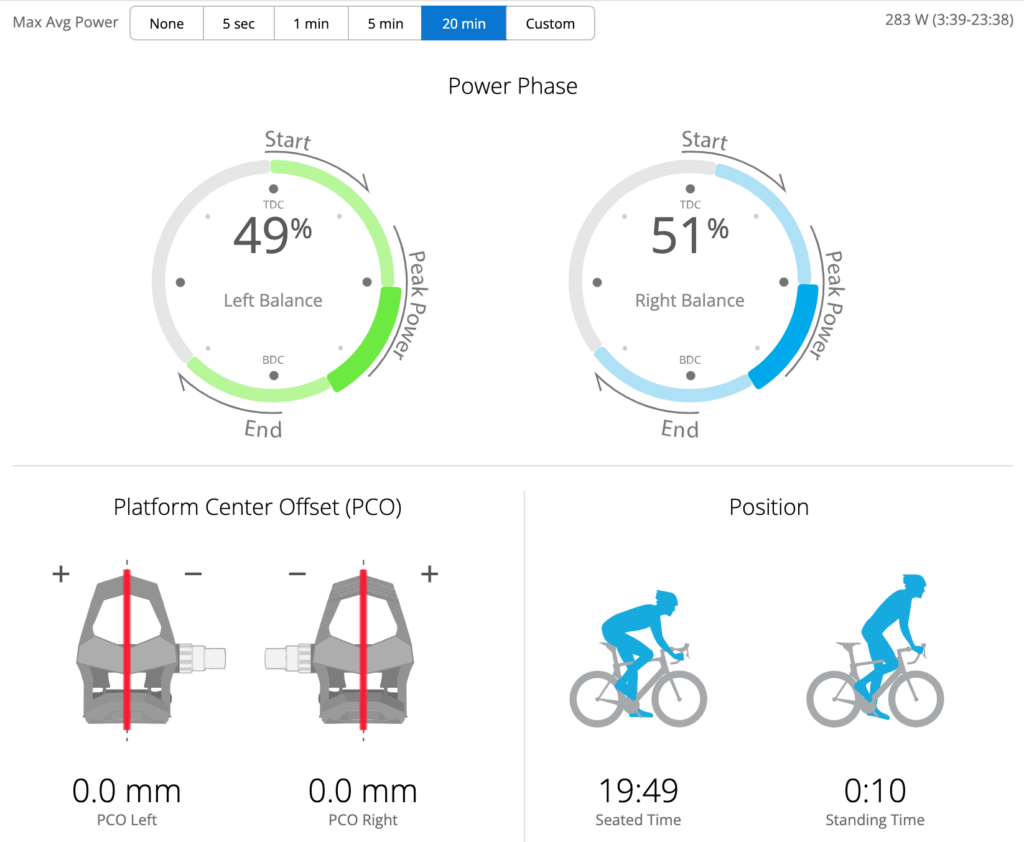

I hit pause for a moment to think about how I’d answer this question. Honestly, I don’t consciously think about pedalling very often whilst riding. On the trainer I do often look at my pedalling dynamics which is a Garmin analytical tool which works with many pedal based power meters.

It’s pretty cool. When I really focus on my pedalling I can eliminate the ‘dead spot’ located at the back (9 o’clock ) position of the power phase. I’ve also spent a lot of time on Power Cranks which are a training tool consisting of cranks with independent clutches in each crank arm. Because of the clutches, each leg is isolated from each other and fully responsible for it’s own side of pedaling. It’s possible to pedal on power cranks with the arms not 180 out of phase with each other. If you ever have a chance, it’s a great experience to ride on these. It will make it glaringly clear how smooth of a pedaller you are. With some dedicated work, you can go on long rides with these cranks, afterwards you notice soreness in your hamstrings due to the requirement to engage them to get the cranks back around on each pedal stroke. What I perceived as pulling up and around the back side of the stroke.

Somewhat related to the power cranks, I also spent some time, and still also have in my parts bin a pair of old school rotor cranks. These featured a cam that accelerated the cranks through the dead spot. So your cranks would also become out phase with each other but it was done automatically for you. Rotor made big claims for the improved efficiency of these cranks, mostly because the dead spot of the power stroke often has a negative contribution to your total power output. The Rotor cranks immediately felt different. It was an odd sensation to have the cranks come out of alignment, but you pretty quickly got used to it. I used these cranks for an off season and some early road races one year and my results were pretty much on par with normal cranks. I don’t think they hurt my power output at all. I found myself wanting to push perhaps one larger gear but at a lower cadence than I might have with traditional cranks. At the time I was racing a lot of kermesse races in Belgium which featured a ton of tight corners and quick accelerations. This wasn’t a great fit for low-cadence ‘dieseling’. I recall that I liked them pretty well in the UCI road races and US criteriums, however. Ultimately though, they were really heavy. Like crazy heavy. I ended up taking them off, but it was an interesting and valuable experience that informed my perceptions of ‘how’ you should efficiently pedal a bike.

So, back to answering the question, “how do you pedal a bike”? When answering this question I thought back to these experiences outlined above and said to myself that when really properly pedalling, it’s super important to focus on the back half of the stroke. With the power cranks, if you don’t do this, you’ll literally be sitting still. The Rotor cranks did this for you, but the perception of the benefit was there. In Europe they talk a lot about souplesse which translates roughly as smoothness or suppleness. Experienced riders tend to have a nice balanced smooth spin. It generally takes years to develop this. Less experienced riders tend to ‘pedal in squares’ and you can see the pedals accelerate on each respective downstroke. A lot of the junior riders on the local Nica MTB team struggle climbing on steep loose terrain. Their tyres tend to slip on the first or second downstroke and then it’s all over and they have to walk. This is almost certainly because they have yet to develop this souplesse and are still ‘pedalling in squares’. I’ve been trying to encourage them to work on smoothing out their pedal stroke, focusing on the entire cycle, in other words spinning in circles for this reason.

After thinking about these things I said to myself that the way I pedal my bike when I do so intentionally is to be really cognizant of pedalling in circles and in particular to think about the back half of the stroke, the weak part of the system and in particular bringing the leg through that dead zone, pulling your leg up through the dead zone, but in a way that emphasises the smoothness of the entire process. As a physicist I know and consider the fact that you want to be applying pressure tangentially throughout the stroke. Radial forces are wasted. But mostly, it’s a pretty automatic thing that I don’t really think about actively most of the time riding.

Much to my chagrin, Colby disagreed. Kind of. In the podcast with Chris, Chris also said that he didn’t really think about pedalling. Colby agreed that this is a really common answer he gets from veteran riders, and riders that he described as ‘super compensators’. These riders tend to be amenable to a variety of bike fit conditions and can jump between bikes with ease even if they aren’t set up identically. This is me, I actually prefer my MTB and road bikes to be setup a bit differently. For example, I like a slightly higher saddle height and more setback on my road bike. Then Colby went on to say ‘at least you didn’t talk about pulling up’.

I was mortified. Well, not actually mortified, but I had a bit of an existential crisis. Is it possible that I’ve been pedalling my bike ‘wrong’ for 30+ years? That’s a long time, certainly I must have learned quite a bit through that time and I even achieved moderate success as a rider. I was in a bit of a conundrum. Should I dismiss what I was listening to, assuming I must know better, or swallow my pride and accept that I might have something to learn, even about something as fundamental and seemingly simple as pedalling a bike? I chose to listen on.

What followed was a fascinating discussion about the dynamics and sensations of pedalling. From a simplified lever system perspective we can elucidate a few key points:

- Your power peak occurs at about 3 o’clock, actually a little past 3 o’clock. This is the most important part of the stroke and where most of the power comes from. We see this in the pedalling dynamics chart above. He then went on to say, never think about this ever again! Why wouldn’t you think about the most important part of the stroke? Well, he said, this is the part of the stroke that evolution took care of for us. We are built and wired to push on the pedals at this part of the stroke. It’s what we get for free. It’s the middle square in the Bingo board. You don’t need to focus on it, literally everyone–from novice to expert–is automatically really good at this. Never speak of it again!

- There is a dead spot, accept this, and accept that you won’t be getting power from it. That doesn’t mean that the dead spot needs to be a negative contribution, you want to avoid pushing against yourself in the part of the stroke, but there isn’t much to gain here.

- The beginning of the power stroke is super important and we want to start this as early as possible. This is achieved by pushing forward on the cranks. Tangentially like I had said. If your saddle is too far forward it’s basically impossible to do this and it delays the early part of the power stroke.

- The bottom of the stroke is equally important. Greg Lemond and most cyclists talk about scraping your leg like you are wiping your feet on a mat on this part of the stroke. Colby suggested instead thinking about driving the heel backwards. He also railed against too high of saddles preventing riders from being able to do this. Most importantly, he suggested that biomechanically we aren’t very good at pulling our legs up, and that the hamstrings are instead evolutionarily optimised to curl your foot towards your buttocks. To take advantage of this focus on the backwards component of this part of the stroke, the curling motion.

He is adamantly against ankling, and the idea of the need for triple extension of your ankle, knee, and femur. Which, I mostly agree with him on. From my experience most riders do not need to ankle. However, I do fee like in the past very short riders often did. As he discussed the problem further I pretty much convinced myself that these shorter riders were mostly ankling to compensate for too long of crankarms. For a long time, crank arms shorter than 165 were very difficult to come by. I used to do a lot of bike fits at a high end road shop in Denver. I never liked the formulae based approach to fitting, and Colby says some similar things. You have to consider the rider holistically, and truly listen to them to achieve a fit that is going to work well. More on this in another post. Colby also said all of this only pedalling discussion only applies to seated riding, which I totally agree with him on. I pedal much differently standing, and much differently standing and climbing vs. standing and sprinting.

So, my world was rocked a little bit. This was quite a bit different from the verbiage I had used to describe how I pedalled. I wondered what it might feel like to concentrate on my pedalling with these suggestions in mind. The next day I had the opportunity to jump on my bike for an endurance pace ride where I could spend some time thinking about this. The result was fascinating. When I focused on pulling up my cranks, truly pulling up, my stroke went to pot. Suddenly it was very jerky and not smooth. What I had previously described as pulling up, was in truth curling back. This is why the power cranks make your hamstrings sore, and not your glutes so much. They require strong hamstring engagement to curl your pedal from the bottom of the stoke back around. This can be done in a way which eliminates any negative force contribution, but in fact is not contributing very much to the torque generated at the bottom bracket. After some time and carefully considering each of his points I decided that Colby’s perspective on proper pedalling wasn’t very much in contrast with my own. However, his description of pedalling was vastly different.

His description is better. Much better. Why, instead of talking to riders about the mystical thing that is souplesse, it’s a much more tangible and descriptive way to explain to new riders about what they should be trying to do. Better words and better teaching methods are super valuable, and I’m grateful for deciding to listen to this pod cast. Did listening to the podcast change the way I pedal a bike? No, not really. Did listening to this podcast fundamentally change the way I talk about pedalling a bike? Yes, absolutely!

Back to the title, pedalling in circles. Do I need to entirely give up on this description of how we ride a bicycle? No, I don’t think so. We are still striving for even smooth power delivery throughout the pedal stroke. However, the souplesse comes not from the contribution of each single leg but instead when we consider both legs working together in tandem. It’s still a circle, but each leg is providing half of it, and when one leg is pushing hardest it comes at the exact moment that the other leg is in the weakest part of it’s stoke.

It’s a collaboration. Even in the case of the Power Cranks where each leg is isolated, the net smooth pedal stroke is only achievable by summing up the contribution of both legs. Only by working together can we pedal in circles.

I did my PhD on liquid phase nuclear magnetic resonance, which is basically the study of how protons in water or hydrocarbon spin in circles in the presence of a magnetic field. Except it isn’t that simple. On an atomic scale the behaviour of each proton is binary, only flipped one way or another. Seemingly chaotic. However, on a macroscopic scale each of these protons contributes and collaborates in such a way that there is a net spinning and coherent magnetic moment. Physicists and doctors use this phenomenon to image things such as human anatomy, or in my case the earth’s subsurface. Through collaboration, billions of very small hydrogen protons can do great things. Together, we are more than the sum of our parts.

What makes a good collaboration? A good collaboration comes when we work together to realise a common goal. When coaching athletes it’s important to realise that it’s not a one way relationship. It’s not merely the coaches job to tell the athlete what they need to be doing. Instead the athletes need to be given sufficient autonomy to work on, explore, and develop what works for them. These experiences then help the coach steer them in the right direction. When we work in groups, collaboration means letting each member contribute their strengths towards the common good. When a single person dominates, it hurts everyone. Effective leadership is therefore more about letting everyone contribute rather than doing the most work. The very best leaders inspire everyone to contribute and may themselves seem to be taking the back seat. This is because they believe in their team. If you are in a leadership position and you do all the work and don’t elicit help from others, you’re likely more a detriment than an asset to your team. I’d encourage you to take a long hard look at your leadership style. No man is an island. As a group member, it’s also critical that we identify our own weaknesses and limitations. This can hurt our egos. Weakness and limitation are relative. Maybe compared to a baby you are quite strong, but compared to the Denver Broncos defensive line, you’re pretty weak. Sometimes expertise creates weakness. We call this expert bias. In the example above I considered pedalling in circles to be the zenith of proper pedalling technique. Honed from years of experience this isn’t incorrect, but it’s a terrible way to describe the process to beginners. In any group or any collaboration, other people are going to be better than you at certain things. Having the humility to accept this makes for effective leadership and will result in superior outcomes. If you aren’t letting everyone meaningfully work and contribute, then you aren’t working together as a team and you aren’t collaborating. We can all work towards doing better at this. If we don’t we risk spinning in circles metaphorically and not making any progress.